- Strategic Drone Use Cases for Australian Agriculture

- 1. Precision Spraying and Variable Rate Application (VRA)

- 2. Autonomous Livestock Monitoring and Mustering

- 3 High-Value Viticulture and Orchard Management

- 4 Broadacre Yield Forecasting and Crop Health Analytics

- The Tech Stack: Sensors, AI, and Connectivity

- Drone Hardware: Picking the Body That Fits the Block

- Sensor Stack: Seeing What Humans Cannot

- AI Processing: Turning Pixels Into Decisions

- Edge vs Cloud Processing: How Data Is Computed in the Field

- Data Sovereignty, Security, and Architecture for AU Agribusiness

- CASA and the Regulatory Landscape

- Where Most Farms Begin

- When Agriculture Becomes Commercial Aviation

- The Real Threshold: Scale and BVLOS

- Chemical Application Requires Its Own Clearance

- What This Means for an Enterprise Building a Drone Program

- Economics and ROI Framework of Drones in Agriculture in Australia

- CAPEX vs Subscription Models

- Three-Year Breakeven Logic

- Labour Hour Offsets

- Water and Chemical Savings

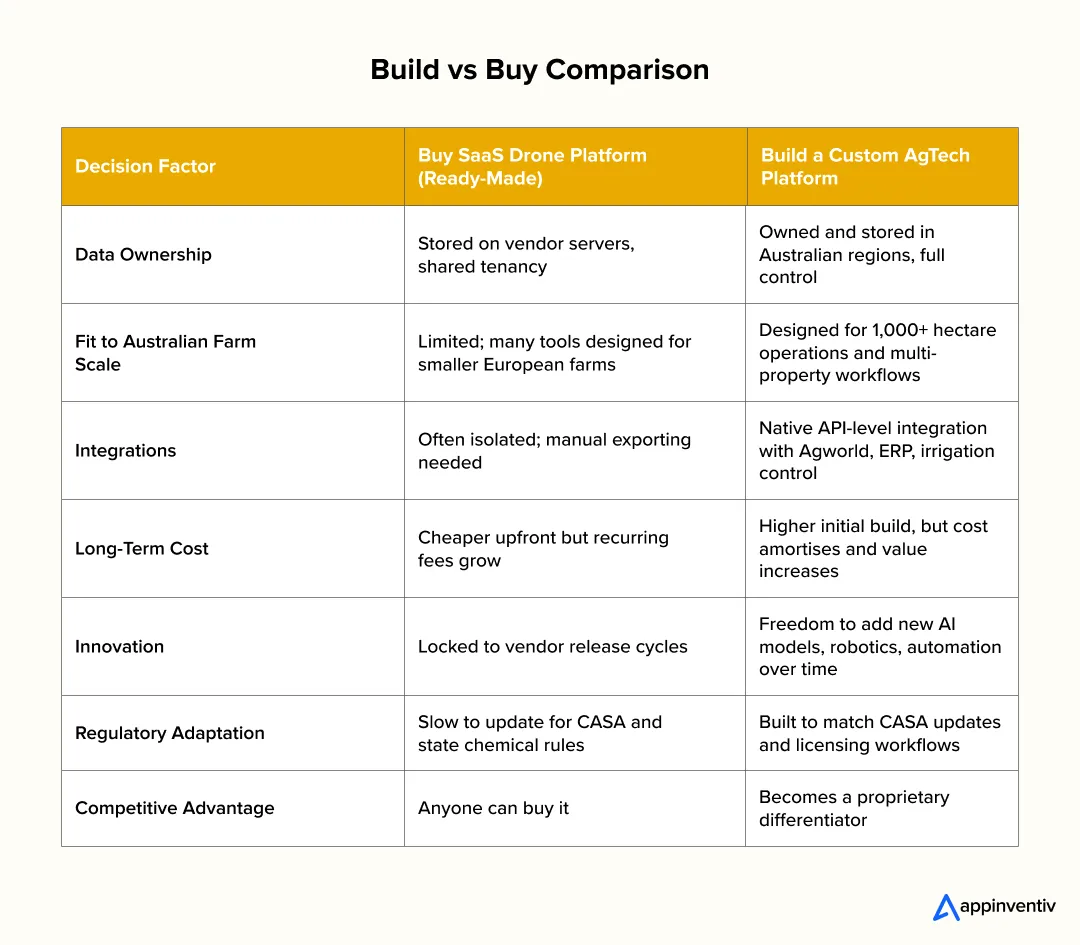

- Build vs Buy for Drone AgTech Platforms

- Challenges in Drone Adoption and Practical Fixes

- Connectivity

- Skills Gap

- Interoperability

- Workflow Discipline

- How Appinventiv Helps Australian Farms Go Digital

- FAQs

Key takeaways:

- Drones are becoming a labour-offset tool for Australian growers, helping large farms operate efficiently with fewer onsite workers.

- The biggest impact comes when drone data is paired with software, AI, and automated workflows, not when drones are used only for visual monitoring.

- Precision spraying, livestock monitoring, vineyard heat-stress mapping, and broadacre yield forecasting are the highest-value use cases delivering measurable results.

- ROI is strongest when farms measure cost per hectare per decision, not the upfront cost of hardware.

- Long-term advantage comes from building a custom digital platform, giving growers ownership of data, integrations, workflows, and scale.

Across Australia, many growers are operating farms that stretch for hundreds of hectares, yet they do not have the workforce they once relied on. According to the latest snapshot from the Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences (ABARES), the sector employs about 255,500 people in 2025, less than 2% of the national workforce, and that proportion continues to decline compared to the scale of agricultural land under management.

The gap between staffing needs and available labour has pushed technology into a more central role, especially the growing use of drones in agriculture in Australia.

Many farms are beginning to use drones in agriculture to cut back the number of hours required to inspect paddocks, assess crop health, or monitor livestock. For growers managing long distances and narrow seasonal windows, agricultural drones have become a practical way to keep operations moving when people are hard to find.

It is less a story of technology replacing people and more about growers needing tools that help them remain competitive with the workforce they have. Drones for agriculture in Australia are becoming part of that operational toolkit. Before we look at how drones are being integrated into farming systems, it is important to understand the labour challenge itself and why it is reshaping the future of agricultural decision making.

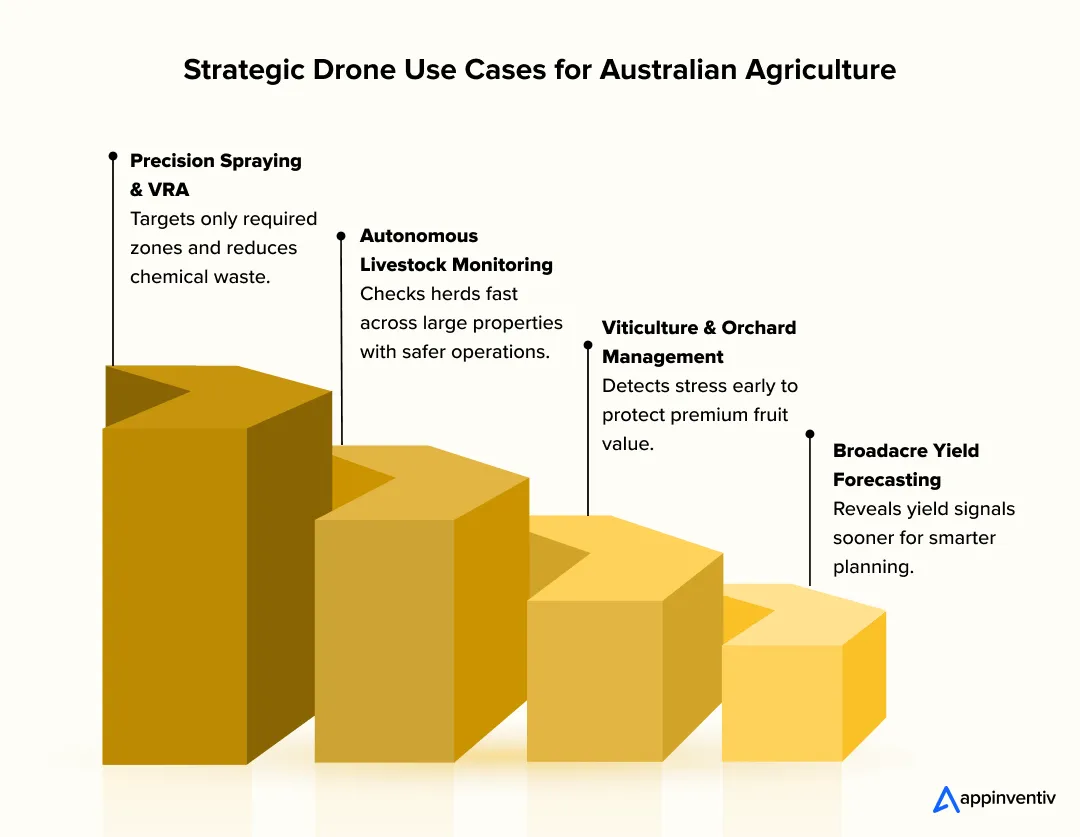

Strategic Drone Use Cases for Australian Agriculture

Agricultural drones are valuable only when they change outcomes on the ground. In Australia, where distances are long and climate pressure moves fast, the strongest use cases sit where time, labour, and seasonal timing intersect. Below are the applications where drones in agriculture in Australia are already changing outcomes.

1. Precision Spraying and Variable Rate Application (VRA)

A key reason drones used in agriculture in Australia are gaining traction is the ability to treat only the land that needs attention instead of applying chemicals blanket-wide. For large cotton, rice, and broadacre grain farms, this creates cost savings and environmental gains.

Why this use case matters

- Chemical prices have increased significantly over the past 24 months

- Input costs are now a top three pressure on growers, according to AgriFutures National Producer Survey 2024

- Labour-light operations need automation, not just visibility

What drones enable

- Auto-generated spray zones based on vegetation index maps

- Precision droplet sizing that reduces drift

- Treatment of isolated weeds without damaging adjacent healthy crop

Example ROI signal: Australia shows tangible savings when farms shift away from blanket spraying. According to FarmTable, targeted drone application and precision spraying approaches can reduce chemical use by up to 30% by treating only the land that requires attention, which directly cuts operational costs and limits unnecessary inputs.

Because chemical inputs are a top cost pressure, this is one of the biggest benefits of drones in agriculture in Australia.

2. Autonomous Livestock Monitoring and Mustering

Australia’s livestock operations face a scale challenge. Cattle stations in the Northern Territory and Queensland often span thousands of hectares, where a single herd check can take hours of travel.

How drones change the equation

- Fly pre-planned livestock count routes in minutes

- Thermal signatures detect sick or isolated cattle quickly

- Muster direction guidance reduces motorbike and vehicle usage

Real-world reference: SkyKelpie, an Australian agtech startup, is pioneering drone-assisted mustering by integrating modern technology to predict herd movement patterns. Making drones for farming a faster way to monitor herds without spending hours crossing properties.

Business impact

- Fewer hours spent on-ground in dangerous terrain

- Lower fuel, quad-bike, and maintenance cost

- Reduction in cattle loss due to late detection

For enterprises, this is a labour-offset use case with safety dividends.

3 High-Value Viticulture and Orchard Management

In vineyards and orchards, small timing errors compound into millions in loss. Grapes, citrus, apples, and stone fruit require visibility at the exact moment stress hits.

What drones make possible

- Canopy modelling using LiDAR to optimise pruning timing

- Heat stress detection before visible wilting

- Fruit load estimation to support logistics and price setting

Australian example: Research shows that UAV-borne multispectral and thermal imagery can detect plant stress indicators for irrigation and water management before physical changes are obvious, which improves precision vineyard management.

This is where drones in farming shift from monitoring to protecting premium value, and where the future of drones in agriculture in Australia is becoming clearer.

4 Broadacre Yield Forecasting and Crop Health Analytics

For broadacre producers managing wheat, barley, oats, canola, and cotton, yield visibility often comes too late. Drones offer earlier insight, by using AI for demand forecasting.

What improves with drones

- NDVI-based stress mapping

- Zone-specific fertiliser placement

- Prediction of harvest tonnage weeks earlier

- Crop emergence validation after planting

Enterprise value: The Australian agriculture drones market is growing rapidly. AI in drone powering data analytics, enabling real-time monitoring of crop health, optimising irrigation and pest management, which helps farmers make informed decisions and improve yields.

Also Read: How AI-Powered Agriculture Apps in Australia are Boosting Farm Gate Returns

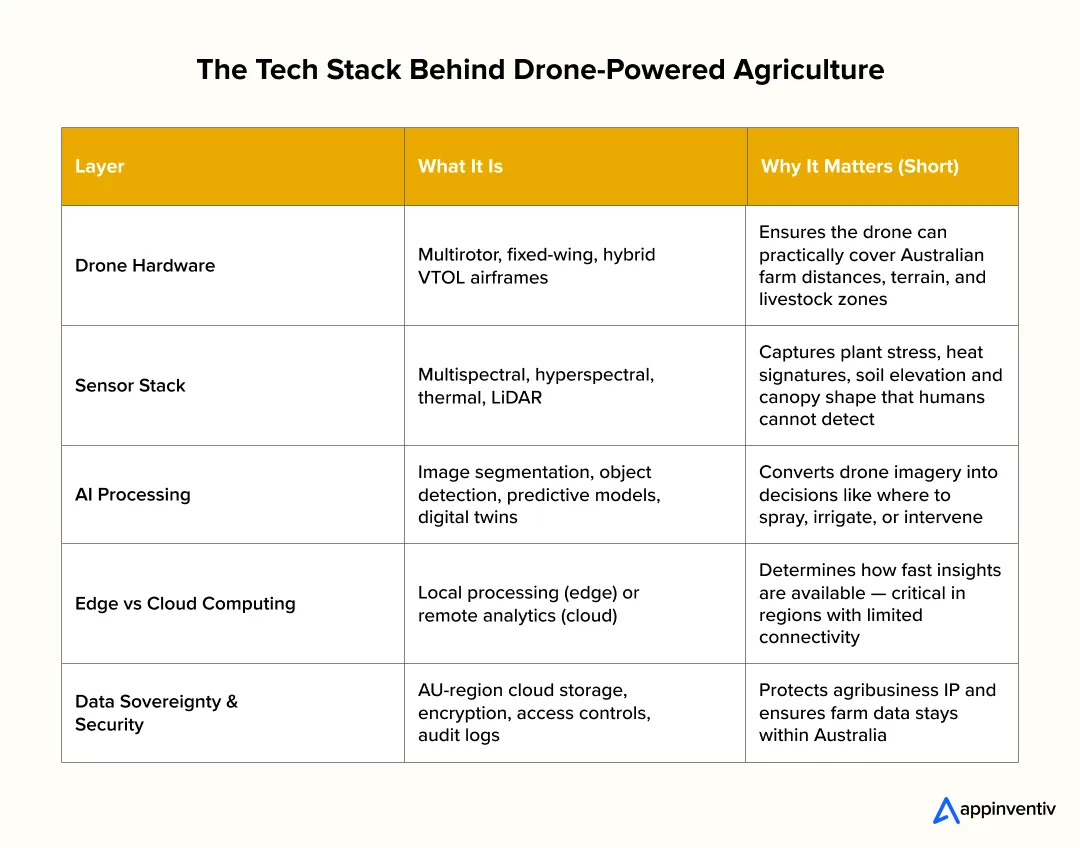

The Tech Stack: Sensors, AI, and Connectivity

Australian agriculture is shifting toward data-driven operating models, where farms are supported by sensing technology, analytics, and integrated systems. CSIRO outlines this shift as a move toward a coordinated system involving sensing, data management, analytics, modeling, and farm system execution.

To understand how drones for agriculture in Australia move from experimentation to enterprise results, it is important to break down the tech stack and the underlying drone technology in agriculture that turns flights into decisions.

Drone Hardware: Picking the Body That Fits the Block

Hardware type determines whether a drone can practically support operations across Australia’s diverse agriculture regions, which is why understanding the types of drones in agriculture matters before selecting fleets.

Types of drones in agriculture

- Multirotor drones: Designed for spot-level monitoring, thermal checks, orchard canopy scans, and small precision jobs. Best suited for horticulture, vineyards, and citrus blocks.

- Fixed-wing drones: High endurance and long-distance flights suitable for broadacre crops including wheat, barley, cotton, and canola. They cover more hectares per battery cycle.

- Hybrid VTOL drones: Take off vertically like multirotors and fly horizontally like fixed-wing. Useful for cattle stations or multi-farm enterprises where flexibility matters.

Why hardware selection matters in Australia

- Farm blocks may exceed 5,000 hectares, meaning multirotors alone may be insufficient

- Remote regions deal with heat, crosswinds, and dust exposure

- Livestock monitoring requires altitude, silent approach, and thermal detection

Hardware is an enabler, not a decision tool. The ROI begins only when sensors and software enter the picture.

Sensor Stack: Seeing What Humans Cannot

Sensors convert drones from flying cameras into agronomic instruments. CSIRO research highlights how modern agriculture depends on sensing combined with analytics and modeling to support insights.

Core sensor types

- Multispectral: Captures reflectance from vegetation to calculate NDVI, NDRE, GNDVI. Useful for crop stress monitoring and disease early identification.

- Hyperspectral: Hundreds of narrow spectral bands, capable of detecting chemical and physiological changes in crops before symptoms appear.

- Thermal infrared: Detects surface temperature differences. Used to identify irrigation failures, livestock body temperature anomalies, and vineyard heat stress patterns.

- LiDAR: Emits laser pulses to create high-precision 3D terrain models. Helps plan erosion controls, irrigation placement, orchard pruning, and canopy uniformity.

Sensor output types produced

- Orthomosaics

- Vegetation indices

- Thermal heat maps

- LiDAR point clouds

- 3D elevation and canopy models

These outputs become the raw ingredients for enterprise data pipelines.

AI Processing: Turning Pixels Into Decisions

Drones alone do not change behaviour. The AI layer is where agricultural drones begin to create intelligence.

What typically happens inside the analytics engine

- Image segmentation: Separating healthy vegetation pixels from stressed zones.

- Object detection: Identifying livestock, weeds, equipment, or erosion lines.

- Time-series change detection: Comparing current orthomosaics with previous scans to show gradual stress.

- Predictive modeling: Estimating yield changes under different environmental conditions.

- Digital twin simulation: Modeling crop growth and water response, similar to CSIRO predictive models used in farm decision tools.

Data formats used in AI pipelines

- GeoTIFF for stitched orthomosaics

- JPG or RAW for RGB imagery

- LAS or LAZ for LiDAR files

- CSV or JSON for metadata and coordinates

Enterprise-grade AI considerations

- Latency: how long between drone landing and usable insight

- AI explainability: can managers understand why the AI recommended a task

- Integration: can outputs feed into ERP, FMS, or spray systems

Edge vs Cloud Processing: How Data Is Computed in the Field

Australia’s rural connectivity problem shapes how drone analytics can work. Large regions of NSW, WA, NT, and QLD have limited coverage.

Two computing models exist

- Edge computing: Processing occurs on drone hardware or nearby gateways. Suitable where connectivity is unreliable.

- Cloud inference: Requires upload to remote servers. Works well for large datasets and long-term storage.

Connectivity enabling drone analytics

- Starlink satellite internet: Now increasingly adopted by rural Australian businesses for real-time analytics uploads.

- LoRaWAN networks: Used for low-power backhaul to transmit small packets such as alerts or detected anomalies.

- 4G/5G rural towers: Where available, allow full-resolution streaming.

Processing time benchmarks

- RGB stitching: 10 to 40 minutes depending on acreage

- Multispectral index rendering: 1 to 2 hours

- LiDAR 3D reconstruction: overnight for large terrain sets

Cloud infrastructure also raises a governance question: where is the data stored?

Data Sovereignty, Security, and Architecture for AU Agribusiness

Data sovereignty matters because agricultural data is strategic. According to CSIRO, digital transformation strategy in agriculture requires trusted data hubs, governance frameworks, and information security that assures producers their data remains protected.

Enterprise expectations

- Data stored within Australian cloud regions

- Role-based access for agronomists, contractors, and corporate leadership

- Retention policies for seasonal records

- Encryption at rest and in transit

- Logs for audit and certification

This is where many growers begin to hire drone software developers in Australia rather than trust generic offshore SaaS dashboards.

CASA and the Regulatory Landscape

If agricultural drones are going to play a permanent role in Australian farming, the rules that govern how they fly cannot be an afterthought. CASA sets the national framework, and while regulations may appear complex on paper, the intent is simple. The skies should stay safe, and operators should understand their responsibility before scaling fleets across thousands of hectares.

For most growers, the first question is where their intended use fits in the system. CASA separates low-risk personal use from commercial operations. That line is what decides whether a farm can simply buy a drone and fly, or whether licences and approvals must sit in place before operations begin.

Where Most Farms Begin

Many farms start under what CASA calls the excluded category. A drone flown on your own land, for your own work, and under 2 kilograms usually requires no formal approval. This is where a grower might run early mapping flights or test a small program without changing their business structure.

The rule changes when a drone becomes part of commercial work. As soon as the operation involves payment, third-party land, staff flying on behalf of a company, or heavier equipment like spray drones, paperwork becomes mandatory.

When Agriculture Becomes Commercial Aviation

Once drones support paid work, or become part of a scaled program, two familiar requirements enter the picture:

- A Remote Pilot Licence (RePL) for the person flying

- A Remotely Piloted Aircraft Operator’s Certificate (ReOC) for the business itself

Both documents are handled through the CASA myCASA portal, along with the Aviation Reference Number that identifies each operator. Most enterprises treat these as upfront prerequisites, not optional extras. Formal approvals protect the organisation just as much as they protect airspace.

The Real Threshold: Scale and BVLOS

Large Australian farms often stretch beyond what a pilot can physically see. That is where Beyond Visual Line of Sight (BVLOS) approvals enter the picture. Without BVLOS, drones must always be flown where the pilot maintains direct sight.

Why BVLOS matters

- Large paddocks or cattle ranges require long-distance flights

- Automated drones cannot be monitored visually

- Multi-farm operators need repeatable flight paths

What approvals typically include

- Defined area map

- Operational procedures

- Safety and recovery plans

Think of BVLOS as the permission that turns a single drone into a fleet that works without supervision.

Chemical Application Requires Its Own Clearance

Flying a camera is one thing. Flying a tank filled with crop chemical is another. Aerial application sits under a mix of CASA rules and state agricultural regulations. Victoria’s ACUP permit and Queensland’s aerial distribution licence are examples of separate state requirements farms must have in place before a spray drone lifts off.

In practice, this step matters because insurance will not protect an operator who applied chemicals without the right authorisation. Large farms handle this risk by treating chemical licences like tractor registration. They are required before the machine is allowed to work.

What This Means for an Enterprise Building a Drone Program

Executives often ask a simple question: will compliance slow us down?

The clearer answer is this. Compliance is a planning step, not a barrier. Most farms that scale drones successfully do the paperwork once, document their procedures, and run the program for years. The bottleneck is rarely CASA. It is unclear internal ownership of who is responsible for keeping licences current.

For a business planning a structured drone program, the smart approach is to appoint one person as the internal operator of record, complete the RePL and ReOC together early, and include CASA lead time in budget and rollout planning.

When onboarding is rushed, the disadvantages of using drones in agriculture usually show up in insurance gaps or delayed approvals.

Also Read: How to Hire Software Developers in Australia

Economics and ROI Framework of Drones in Agriculture in Australia

The financial case for drones in agriculture in Australia only makes sense when numbers are clear. For enterprise farms, drone adoption is not a gadget purchase. It is a capital allocation decision that must prove its return against labour savings, input reduction, and risk protection across multiple seasons.

CAPEX vs Subscription Models

Most farms begin by purchasing one drone outright. Larger operations eventually shift to a recurring software and analytics model. The balance between capital expense and subscription determines how quickly ROI is realised.

CAPEX characteristics

- One-time cost for hardware

- Best for small farms or trial programs

- Value is limited without software integration

Subscription or service model

- Monthly or seasonal fee that includes analytics, processing, dashboards, and sometimes pilot services

- Predictable budgeting for CFOs

- Scales more easily when multiple farms share a platform

For many enterprises, the real cost sits not in the drone, but in the software, training, and integration needed to make the drone useful at scale.

Subscription models also make drones for agriculture in Australia accessible for mid-scale operators that need flexibility before committing long term

Three-Year Breakeven Logic

A three-year view works because drones have hardware lifespans, and cropping cycles allow multiple seasons of benefit.

The breakeven point usually appears when labour hours saved and chemical inputs reduced outweigh the cost of equipment and software.

Breakeven drivers

- Hours of scouting avoided each month

- Chemical waste prevented through precision spraying

- Avoided yield losses from earlier disease detection

- Fuel and vehicle depreciation avoided through livestock monitoring

If these benefits line up, most drone programs breakeven well before year three, even with subscription software added on top.

Labour Hour Offsets

Labour offsets are the clearest, most immediate gains. One drone flight often replaces several hours of walking, driving, or quad-bike monitoring.

Examples of labour reduction

- 1 drone operator can survey 500 hectares in a fraction of the time previously required

- Livestock checks that once took 3–4 staff can be completed by one pilot with one drone

- Agronomists can prioritise high-risk zones instead of visiting every paddock

CFOs often see labour offsets as the most reliable input in ROI calculations because they are measurable from week one.

Water and Chemical Savings

Input efficiency has become a priority as chemical costs rise and water restrictions tighten. Precision treatment enabled by agricultural drones reduces over-application, particularly in broadacre farms.

Where savings come from

- Treating only the zones that require attention

- Avoiding unnecessary irrigation in heat-stressed patches

- Reducing runoff and drift that damages adjacent crops

Below is a simple reference table to compare baseline vs drone-supported treatment.

| Metric | Traditional Practice | Drone-Assisted Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Application | Blanket spraying across entire field | Variable rate zones based on mapped stress |

| Chemical Waste | 10 to 20% common in broadacre | Typically below 3% after VRA |

| Water Use | Uniform irrigation regardless of need | Sensor-triggered irrigation in required patches |

| Input Cost Curve | Grows with acreage | Scales more slowly due to precision |

Build vs Buy for Drone AgTech Platforms

Once a farm or agribusiness decides drones will play a long-term role, the next strategic question is whether to invest in software of their own or rely on off-the-shelf drone dashboards.

Buying feels faster in the beginning, especially for testing drone technology in agriculture, but it rarely fits the way Australian farms operate at scale. Build becomes the path when the goal is not scanning paddocks, but running an integrated business.

Why this decision matters

- Drone hardware becomes a commodity, but software defines who owns the data, who controls the logic, and who can innovate faster than competitors

- Off-the-shelf platforms make enterprises dependent on vendor roadmaps

- A custom digital layer becomes an asset that appreciates in value as the business evolves

Also Read: Software Development Cost in Australia

Challenges in Drone Adoption and Practical Fixes

Even the smartest drone strategy can stall if a few predictable obstacles are ignored. Most failures do not come from the drone. They come from systems, skills, and habits. Below are the four friction points that repeatedly slow adoption of drones in agriculture in Australia, and the practical fixes that help farms move past them.

Connectivity

Remote paddocks and large cattle regions often operate with weak or inconsistent network coverage. This affects data upload speed, real-time monitoring, and access to dashboards.

The problem

- Data cannot upload, delaying insights

- Field teams cannot view maps without internet

- Automated flights cannot sync

Mitigation

- Deploy Starlink or private LoRaWAN networks in remote zones

- Use hybrid data pipelines: process images at the edge, sync when back in signal

- Build offline-first mobile apps so data is stored locally and uploads later

Skills Gap

Many farms own drones but rarely fly them. The gap is usually not interest, but confidence and capability.

The problem

- Staff do not know who should fly or when

- Agronomy teams struggle to interpret analytics

- No owner is assigned to the drone program

Mitigation

- Nominate a single internal Drone Ops lead

- Provide structured training for pilots and agronomists

- Build dashboards that translate insights into simple “do this next” tasks

Interoperability

Data becomes useless when it is trapped inside a standalone system. Interoperability is the biggest reason enterprise drone programs either scale or disappear.

The problem

- Drone outputs do not plug into Agworld, ERP, or irrigation systems

- Staff must manually convert data into jobs

- No feedback loop exists for learning or yield prediction

Mitigation

- Use API-driven architecture from day one

- Build a digital operating layer that sits between data sources and execution tools

- At minimum: ensure drone maps can export into the tools managers already use

Workflow Discipline

Technology only works when people use it consistently. Farms often fly drones when they have time, not when the land needs attention.

The problem

- Inconsistent scans lead to reactive decisions

- Tasks pile up because no system assigns ownership

- Leaders cannot forecast because data is missing

Mitigation

- Set fixed scan schedules tied to crop stage or livestock cycle

- Automate job creation so insights always become work

- Make dashboards part of daily meetings, not optional review

How Appinventiv Helps Australian Farms Go Digital

Australian agriculture is shifting from manual oversight to data-led operations, where using drones in farming is becoming a baseline expectation rather than a differentiator. Drones in agriculture in Australia provide the initial visibility, but real transformation only happens when those insights connect to software, automation, and planning systems that run every day, not just on scan days.

Appinventiv supports that shift through agriculture software development services that help growers move from trial-based drone use to fully integrated digital operations. With 10+ years of APAC delivery experience, 96% client retention, and more than 250 digital assets deployed across Australia, our approach focuses on building technology that is practical, easy to use, and aligned to how farms actually work.

The farms that strengthen margins over time will be the ones that shorten the gap between what the land shows and how fast decisions follow.

Ready to explore what a digital solution could look like for your farm? Speak to our AgTech consulting team to map the first step.

FAQs

Q. What AI technologies are used in agricultural drones?

A. Agricultural drones in Australia typically rely on computer vision, multispectral image processing, and predictive analytics models that detect crop stress, map soil variability, and forecast yield. At scale, drones in agriculture in Australia also use machine learning algorithms to classify plant health, thermal AI to flag water stress, and digital twin engines that simulate crop outcomes under different environmental conditions. These systems help growers move from visual inspections to automated, data-supported decisions.

Q. How are drones used in agriculture in Australia?

A. Drones are now part of daily farm workflows across cropping and livestock regions. They support zone-based scouting, broadacre heat-stress mapping, and herd checks without vehicle travel. Some properties also deploy spray drones in agriculture where variable-rate spraying replaces blanket chemical application. Their role is becoming more operational and less experimental, particularly in regions facing workforce shortages.

Q. What are drones used for in agriculture?

A. If you are wondering What are the most impactful drone use cases for Australian growers? At a practical level, drones help growers save time and reduce wasted effort. They scan crops faster than ground teams, identify early-stage disease, validate emergence after planting, and support livestock monitoring on remote paddocks. One of the strongest benefits of drones in agriculture Australia is that they turn problems into data points that can be actioned immediately, rather than discovered too late in the season.

Q. What is the ROI of using drones in Australian agriculture?

A. Return on investment typically shows up in reduced labour hours, lower chemical inputs, and avoided losses from heat or disease stress that previously went unseen. Many CFOs first compare the cost of agricultural drones in Australia to seasonal labour and fuel costs, then expand ROI calculations to include avoided spoilage and improved yield. When drone data flows into software and teams act on it consistently, the financial return tends to compound season over season, making drone technology in agriculture a long-term asset rather than a one-time purchase.

- In just 2 mins you will get a response

- Your idea is 100% protected by our Non Disclosure Agreement.

How To Build a Farm Management Software in Australia?

Key takeaways: Strategic roadmap on how to build a farm management software in Australia that aligns with multi-site, multi-entity farm operations. Explains core modules like farm mapping, livestock, inventory, workforce, finance, and ESG to create one unified operational source of truth. Breaks down the complete development journey from vision, domain modelling, and architecture to MVP,…

How AI-Powered Agriculture Apps in Australia Are Boosting Farm Gate Returns

Key takeaways: AI-powered agriculture apps in Australia are no longer productivity tools alone. When built around farm gate economics, they become decision infrastructure that directly influences cost control, quality consistency, and pricing outcomes. Traditional yield growth is insufficient under rising input costs and market volatility. AI-led agriculture platforms create value by improving timing, quality thresholds,…

How Technology in Agriculture Continues to Empower Farmers

The agriculture industry has seen multiple revolutions over the last 50 years. The advancements in agriculture, specially in machinery has, over time, expanded the speed, scale, and farm equipment productivity - leading to better land cultivation. Today, in the 21st century, agriculture has found itself in the center of yet another revolution. An agricultural technology…